The Hog Industry Strikes Back

Swine flu H1N1 appears at one and the same time moving full-boar and on its cloven heels. The World Health Organization reports 15,510 official cases in 53 countries, with new countries regularly reporting in. An order or two more cases are likely unreported and together represent an atypical spring surge for influenza. At the same time, the strain’s virulence appears presently no more than along the lines of a bad seasonal influenza.

Swine flu H1N1 appears at one and the same time moving full-boar and on its cloven heels. The World Health Organization reports 15,510 official cases in 53 countries, with new countries regularly reporting in. An order or two more cases are likely unreported and together represent an atypical spring surge for influenza. At the same time, the strain’s virulence appears presently no more than along the lines of a bad seasonal influenza.

One of the mistakes we need avoid is to assume we’ve been victimized by a media-fueled hysteria. Given the mortality rates reported at the beginning of the outbreak in Mexico—exceeding that of the 1918 pandemic—it looked like we were in for it. Previous pandemics teach us that preparing for the worst is the prudent option. Imagine the reaction if only feeble preparations were made in the face of a truly deadly pandemic. The cost of a Type II error, thinking no pandemic possible with one imminent, is catastrophically greater than that of its Type I sibling, thinking a pandemic imminent with none in the offering.

A second mistake is to accept any ‘all-clear’ at face value. Swine flu H1N1 may be for most of those infected a relatively mild influenza now, but we’re still not sure how it all will play out. The virus is undoubtedly evolving as it spreads and may reassort enough with other strains to eventually produce a strain infectious and deadly. In other words, whether the new H1N1 continues to mimic the effects of seasonal influenza as it diffuses remains very much an open question.

History offers a warning written in bloody spittle. The 1918 pandemic proved mild in its spring incarnation and apocalyptic the following fall. But even then there remained great variation in the pathogen’s effects across the population: some people were exposed but not infected, some were infected but suffered only a seasonal-like flu, and then, of course, there were those whose viscera melted from the inside out. A case fatality rate clocking in at 5%—a comfort only to the most perverse of today’s naysayers—killed 50-100 million people worldwide.

We are far from the clear for another reason, one finely stitched into the fabric of modern life. There now circulates a veritable zoo of influenza subtypes that have proven themselves capable of infecting humans: H5N1, H7N1, H7N3, H7N7, H9N2, in all likelihood H5N2, and perhaps some of the H6 series. Think hurricanes. We may have dodged one here and yet even now an Influenza Katrina may be gathering its skirts in the epidemiological queue.

A burgeoning variety of new influenza subtypes capable of infecting humans appears the result of a concomitant globalization of the industrial model of poultry and pig production. Since the 1970s vertically integrated stockbreeding has spread out from its origins in the southeastern United States across the globe. Our world is encircled by cities of millions of monoculture pig and poultry pressed alongside each other, an ecology nigh perfect for the evolution of multiple virulent strains of influenza.

Not a pleasant picture, indeed grounds for ending the bizarre cultural practice of stuffing thousands of inbred animals under the same roof. But unraveling the globalization of vertical agribusiness already more than fifty years in the making will take more than realizing it was a bad idea. Big Food likes making big bucks and aims to protect a racket it took so long to corner. Efforts to test for ties between agribusiness and protopandemic influenza are a threat to such a hard-won competitive advantage.

*

So the hog industry has struck back. It successfully lobbied the World Health Organization to rename the swine flu by a scientific name, H1N1, with its confusing connotations of seasonal H1N1.

This isn’t the first time WHO has caved to political pressure over nomenclature. In 2007, WHO implemented a new naming system for the various strains of influenza A (H5N1), the bird flu virus circulating through Eurasia, Africa and Oceania. The H5N1 strains are now enumerated rather than labeled after their countries or regions of origin. The ‘Fujian-like’ strain, first named after its southern Chinese province of origin, is now called ‘Clade 2.2.4’.

WHO declared the new H5N1 names necessary because of the confusion caused by disparate systems used in the scientific literature. A unified system of nomenclature would facilitate the interpretation of genetic and surveillance data generated by different labs. It would also provide a framework for revising strain names based on viral characteristics. The new system would at the same time bring an end to the ‘stigmatization’ caused when flu strains are named after their places of origin.

The changes also represented an attempt on the part of WHO to placate member countries that are currently sources for many of the new bird flu strains. Without these members’ cooperation, WHO would have no or little access to H5N1 isolates from which genetic sequences and possible vaccines can be derived. WHO’s appeasement, however, never stopped China, H5N1’s place of birth, from laying a veritable quarantine around scientific information about bird flu there. Only a few genetic sequences from Chinese H5N1 have been made publicly available since 2006.

The new names also peal back causality to the biomedical. Influenza can indeed be defined by its molecular structure, genetics, virology, pathogenesis, host biology, clinical course, treatment, modes of transmission, and phylogenetics. Such work is, of course, essential. But limiting investigation to these topics misses critical mechanisms that are operating at other broader levels of socioecological organization. These mechanisms include how livestock are owned and organized across time and space. In other words, we need to get at the specific decisions specific governments and companies make that promote the emergence of virulent influenza. Thinking virological alone disappears such explanations, very much in the hog industry’s favor.

For swine flu H1N1, industrial hog are to blame, even if the full story eventually proves to be more complex. As reported by the CDC, multiple genomic segments of the new influenza are derived from hog influenzas,

[T]he majority of their genes, including the hemagglutinin (HA) gene, are similar to those of swine influenza viruses that have circulated among U.S. pigs since approximately 1999; however, two genes coding for the neuraminidase (NA) and matrix (M) proteins are similar to corresponding genes of swine influenza viruses of the Eurasian lineage… This particular genetic combination of swine influenza virus segments has not been recognized previously among swine or human isolates in the United States, or elsewhere based on analyses of influenza genomic sequences available on GenBank.

A recent Science report makes an even stronger claim, “[T]he closest ancestral gene for each of the eight gene segments is of swine origin…”

No small farmer has the industrial capacity necessary to export live livestock of any consequence across countries, nor the market entree livestock influenza needs to spread through an international commodity chain. And yet the hypothesis the hog industry is responsible has been treated as nigh-paranormal. An April 30 Reuters report grouped the possibility with the wackiest conspiracy theories that could be trolled from the internet:

Dead pigs in China, evil factory farms in Mexico and an Al Qaeda plot involving Mexican drug cartels are a few wild theories seeking to explain a deadly swine flu outbreak that has killed up to 176 people.

Nobody knows for sure but scientists say the origins are in fact far less sinister and are likely explained by the ability of viruses to mutate and jump from species to species as animals and people increasingly live closer to each other.

The report begs by what means animals and people find themselves increasingly living together. The reporters don’t bother. At some point, however, the abstract must be instantiated in the acts of particular people in particular localities. Those ‘evil’ factory farms arrayed along rural and periurban bands encircling Mexico City, one of the world’s largest city, may very well have something to do with the start of this particular pandemic and warrant serious investigation. (For details see the nearby maps described at the end of this post.)

The Reuters report continues,

[I]n Mexico reports in at least two newspapers focused on a factory farm run by a subsidiary of global food giant Smithfield Foods. Some of the rumors mentioned noxious fumes from pig manure and flies — neither a known vector for flu viruses.

Those reports brought a swift reply from the biggest U.S. hog producer.

“Based on available recent information, Smithfield has no reason to believe that the virus is in any way connected to its operations in Mexico,” the company said in a statement.

A lawyer’s careful answer. Funny, though, that at the time of the initial outbreak in Veracruz Smithfield dismissed local residents’ concerns about illnesses from the company’s pollution at its Granjes Carrol subsidy outside Perote, near a major highway and only a half-day’s ride from Mexico City, as likely the outcome of ‘flu’. One wonders what Smithfield now blames those illnesses on now that it’s taken flu off the table.

*

We named this strain of influenza after NAFTA to address the broader neoliberalism directed at forcing vertically integrated husbandry onto Mexico at the expense of small farmers. No one company need be blamed in full. But what if this particular influenza strain arose on Smithfield’s lots? Contrary to Reuters’ attempts to submarine a genuine possibility based on material facts on the ground—rather than conspiracies spun wholesale out of naught but paranoiac fantasy—the Food and Agriculture Organization is taking Smithfield’s putative role seriously enough to dispatch a team to Mexico to investigate.

We named this strain of influenza after NAFTA to address the broader neoliberalism directed at forcing vertically integrated husbandry onto Mexico at the expense of small farmers. No one company need be blamed in full. But what if this particular influenza strain arose on Smithfield’s lots? Contrary to Reuters’ attempts to submarine a genuine possibility based on material facts on the ground—rather than conspiracies spun wholesale out of naught but paranoiac fantasy—the Food and Agriculture Organization is taking Smithfield’s putative role seriously enough to dispatch a team to Mexico to investigate.

In a preemptive strike, Smithfield CEO Larry Pope announced the company’s Veracruz pigs clean of H1N1,

I am pleased to report that the results of the testing process conducted by the Mexican government have confirmed that no virus, including the human strain of A(H1N1) influenza, is present in the pig herd at Granjas Carroll de Mexico (GCM), our joint venture farm in Veracruz, Mexico. These findings, which are consistent with our earlier communications to you, validate what we believed from the very beginning: that the recent subtype of H1N1 influenza virus affecting humans did not originate from GCM.

The Mexican government went so far as to claim no disease anywhere in Mexico, “Following repeated investigations, Mexico’s 15 million pigs are all healthy and ready to eat, according to Agriculture Minister Alberto Cardenas.”

But such certification, to which we will return, is often a political football, with accreditation and rejection dependent on the state of this week’s trade battle. As recently as this past December, Cardenas blocked imports from Smithfield and other U.S. agribusinesses,

Mexico, a major buyer of U.S. meat, suspended shipments from 30 U.S. beef, lamb, pork and poultry plants as of Dec. 23, citing factors like packaging, labeling and transport conditions. It cleared 20 of them on Monday after the USDA reported corrective actions had been taken…

Mexican Agriculture Minister Alberto Cardenas told reporters the government was stepping up sanitary controls to keep contaminated meat out of Mexico…

U.S. analysts have said the bans were likely because of Mexico’s opposition to a recently enacted meat labeling law. Mexico and the U.S. Agriculture Department have both denied the retaliation charge.

Plants owned by Tyson Foods Inc (TSN.N), Smithfield Foods Inc (SFD.N), JBS (JBSS3.SA) and privately owned Cargill Inc are among the plants cleared for export to Mexico, including Smithfield’s Tar Heel, North Carolina, pork plant, the world’s largest, according to a USDA report…

Mexico is the top export market by volume for U.S. beef, veal and turkey, the second largest for pork, and the third largest for chicken, according to U.S. government statistics.

Smithfield’s latest health certification begs a number of questions. Was H1N1 absent in all Veracruz pigs several months ago, as far back as early February when locals began to become ill? How to account for Edgar Hernandes, the Xaltepec four-year-old, the first confirmed H1N1 case in Mexico? Hernandes appeared no anomaly. Mexico’s General Directorate of Epidemiology reported an early April outbreak of influenza-like illness in Veracruz weeks before the virus spread outward. How did an influenza with a variety of swine-source genomic segments from around the world originate other than via the swine trade? Is Smithfield instead prepared to blame other companies? Smithfield owns eight large swine farms in the area in which the pathogen appeared to have emerged as a human infection. Could this all be coincidence alone?

According to Smithfield, yes. As a Smithfield manager put it, “What happened in La Gloria was an unfortunate coincidence with a big and serious problem that is happening now with this new flu virus.” That’s no explanation whatsoever. The company appears perfectly comfortable with erasing the notion of cause and effect.

Now it may turn out that Smithfield isn’t to blame for this particular outbreak after all. Swine flu H1N1’s origins may extend far spread beyond any one country’s borders. Ruben Donis, CDC’s chief of molecular virology and vaccines, suggested that the virus,

may have originated in a U.S. pig that traveled to Asia as part of the hog trade. The virus may have infected a human there, who then traveled back to North America, where the virus perfected human-to-human spread, maybe even moving from the United States to Mexico.

It’s a logically plausible possibility, consistent with the hypothesis that the geographic extent of influenza’s multiple reassortants now extends across the globe. But such a possibility doesn’t preclude investigation of the simplest explanation—that the final viral phenotype from a series of reassortment events emerged in the locality where it caused the first human cases. Moreover, it’s a reasonable hypothesis that accelerated reassortment may have been promoted by a fundamental shift in the ownership structure of area farms.

Smithfield entered Mexico the year NAFTA went into effect. The company consolidated small farms outside Perote, opening Carroll Ranches through a new subsidiary corporation, Agroindustrias de México. In Mexico Smithfield avoided the regulation to which the company has been increasingly subjected in the United States. In 1997 Smithfield was fined $12.6 million for violating the U.S.’s Clean Water Act. Missouri residents are now suing Smithfield for pollution. The feds are now investigating a Smithfield farm in Pennsylvania for releasing pig sewage into local waters in 2007. In contrast, according to La Jornada, Carroll Ranches, processing 800,000 pigs annually, is presently under no obligation to subject its swines’ feces, tons produced daily, to sewage treatment.

Smithfield has globalized such practices. In something of an instant classic, the New York Times’ Doreen Carvajal and Stephen Castle wrote of Smithfield’s East European campaign and its epidemiological effects,

Smithfield’s global approach is clear; its chairman, Joseph Luter III, has described it as moving in a “very, very big way, very, very fast.” In less than five years, Smithfield enlisted politicians in Poland and Romania, tapped into hefty European Union farm subsidies and fended off local opposition groups to create a conglomerate of feed mills, slaughterhouses and climate-controlled barns housing thousands of hogs.

It moved with such speed that sometimes it failed to secure environmental permits or inform the authorities about pig deaths — lapses that emerged after swine fever swept through three Romanian hog compounds in 2007, two of which were operating without permits. Some 67,000 hogs died or were destroyed, with infected and healthy pigs shot to stanch the spread…

“For them, it’s like dealing with primitive people in the bush, where only power and strength is important,” said Emilia Niemyt, the mayor of Wierzchkowo, a Polish village of 331 people that has pressed complaints about odors. “They fulfill the idea of conquering the East with the methods of the Wild West.”

The article, required reading, offers a blow-by-blow account of the regional exercise of Smithfield’s political power.

That power extends into the politics of a pandemic above and beyond the name of the virus. Mexico exonerated Smithfield’s Veracruz operations on the basis of 30 swine samples chosen by Smithfield itself. A few samples volunteered by the very company under scrutiny do not serve as the basis of the rigorous and unbiased testing one would expect for a worldwide pandemic. As put by blogger Tom Phillpot, who has been terrific debunking agribusiness flack around the outbreak,

For a lobbyist working the Hill on behalf of an industry, the gold standard is self-regulation. No need to send in inspectors—we’ll test our process to ensure that it doesn’t pollute. Trust us!

Astonishingly, pork giant Smithfield Foods has evidently managed to arrange just such a testing regime with regard to its hog-rearing operations in Vera Cruz, Mexico—some of which lie just a few miles from the village where the swine flu outbreak first manifested itself.

Despite hosting billions of pigs and poultry, the governments around the world offer no systematic testing and regulation. In the U.S., no system is in place beyond that offered on the drawing board. According to the CDC,

[No] formal national surveillance system exists to determine what viruses are prevalent in the U.S. swine population. Recent collaboration between the U.S. Department of Agriculture and CDC has led to development of a pilot swine influenza virus surveillance program to better understand the epidemiology and ecology of swine influenza virus infections in swine and humans.

Contrast the hysteria over bioterrorism since 9/11 with the millions of influenza suitcase bombs crapping themselves as they’re trucked uninspected across borders.

*

The hog industry’s most brazen gambit is to blame people for threatening pigs with flu,

“That is the biggest concern, that your herd could somehow contract this illness from an infected person,” said Kansas hog farmer Ron Suther, who is banning visitors from his sow barns and requiring maintenance workers, delivery men and other strangers to report on recent travels and any illness before they step foot on his property…

“There is no evidence of this new strain being in our pig populations in the United States. And our concern very much is we don’t want a sick human to come into our barns and transmit this new virus to our pigs,” said National Pork Producers chief veterinarian Jennifer Greiner.

“If humans give it to pigs, we don’t have things like Tamiflu for pigs. We don’t have antivirals. We have no treatment other than to give them aspirin,” said Greiner.

For now let’s set aside Greiner’s attempt to disappear the evidence several of the new strain’s genomic segments originated from a recombinant H3N2/H1N1 influenza that has circulated among U.S. swine since 1998. The evidence for human-to-pig infection is at best circumstantial. Canadian Press medical reporter Helen Branswell writes,

There is no smoking gun in the case of the H1N1 infected pigs – and authorities investigating the first known infections of pigs with this new swine flu virus may not be able to unearth one, a senior Canadian Food Inspection Agency official admits.

Testing of people on the farm – some of which was done too late, some of which may not have used the best technique to get an answer – has turned up no solid proof people brought the virus to the pigs. And it remains to be seen whether blood testing will be able to fill the evidence gap.

So the industry’s ploy has little leg to stand on. But even if the bald assertion proves true, it acts only as a damning admission of the nature of influenza traffic between host types. For now, the assertion stands as a monument to the hubris of an industry shameless enough to blame the victims of its own standard practices.

With public health officials, reporters and PR flacks burying leads and manufacturing diversions in their stead, the rationale for investigating the roles confined animal feedlot operations play in the emergence of pandemic influenzas may—poof!—disappear. The next few months may very well demonstrate that being a well-connected global conglomerate means never having to say you’re sorry no matter the damage caused. It is, after all, the kind of protection for which the hog industry has paid.

The infrastructure of such political influence requires both time and care (and enough cash) to build. As Carvajal and Castle report,

Smithfield fine-tuned its approach in the depressed tobacco country of eastern North Carolina in the 1990s. In 2000, money started flowing from a Smithfield political action committee in that state and around the United States. Ultimately, more than $1 million went to candidates in state and federal elections. North Carolina lawmakers helped fast-track permits for Smithfield and exempted pig farms from zoning laws.

With increasing restrictions in the U.S., Smithfield,

took its North Carolina game plan to Poland and Romania, where the company moved nimbly through weak economies and political and regulatory systems…

Once the top leaders in Romania showed their support for Smithfield, developments fell into place; about a dozen Smithfield farms were designed by an architectural firm owned by Gheorghe Seculici, a former deputy prime minister with close ties to President Traian Basescu of Romania, who is godfather to his daughter.

Further help came from a familiar front: Smithfield’s lobbyist, the Virginia firm McGuireWoods, set up a Bucharest office in 2007 to liaise between Smithfield and the Romanian government. In many ways McGuireWoods was the perfect choice; it had also represented Romania for three years to press its NATO-membership campaign…

The connections in the upper reaches of government meant that Smithfield could weather protests from local communities.

Attempts to proactively change poultry production in the interests of stopping pathogen outbreaks can be met with severe resistance by governments beholden to their corporate sponsors. In effect, influenza, by virtue of its association with agribusiness, has some of the most powerful representatives available defending its interests in the halls of government. In covering up or downplaying outbreaks in an effort to protect quarterly profits, these institutions contribute to the viruses’ evolutionary fortunes. The very biology of influenza is enmeshed with the political economy of the business of food.

If multinational agribusinesses can parlay the geography of production into huge profits, regardless of the outbreaks that may accrue, who pays the costs? The costs of factory farms are routinely externalized. As Peter Singer explains, the state has long been forced to pick up the tab for the problems these farms cause; among them, health problems for its workers, pollution released into the surrounding land, food poisoning, and damage to transportation infrastructure. A breach in a poultry lagoon, releasing tons of feces into a Cape Fear tributary, causing a massive fish kill, is left to local governments to clean up.

With the specter of influenza the state is again prepared to pick up the bill so that factory farms can continue to operate without interruption, this time in the face of worldwide pandemics agribusiness helps cause in the first place. The economics are startling. The world’s governments are prepared to subsidize agribusiness billions upon billions for damage control in the form of animal and human vaccines, Tamiflu, culling operations, and body bags.

Even an appeal to preserving greed’s global reach falters. Along with the lives of a billion people, the establishment appears willing to gamble much of the world’s economic productivity, which stands to suffer catastrophically if a more severe pandemic were to erupt. Criminally negligent and politically protected myopia pays, until it doesn’t. Then someone else picks up the bill.

It is perhaps cliché to evoke the fates of lost empires. And yet Edward Gibbon’s eulogy encapsulates our moment in both its spirit and its particulars,

The forum of the Roman people, where they assembled to enact their laws and elect their magistrates, is now enclosed for the cultivation of pot-herbs, or thrown open for the reception of swine…

In our case, however, pastoral infestation appears the means to a ruins and not its aftermath.

*

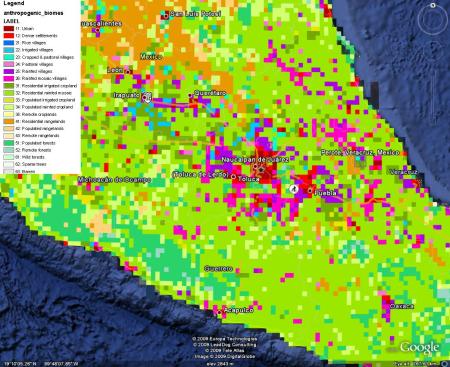

Images: Top image shows the distribution of anthropogenic biomes in and around Mexico City. The map of ‘anthromes’ worldwide, developed by Erle Ellis and Navin Ramankutty, is available as a Google Earth overlay. The red in the middle is Mexico City proper, the purples and pinks rainfed villages, and the greens residential rainfed and irrigated croplands. But it’s the orange-brown that we’re interested in most here. These are the residential rangelands where grazing domestic animals are situated with alongside more than 10 people per km2, areas of intensive human-domestic animal contact. Most of this anthrome is situated north of Mexico City, one of the world’s largest cities and plugged right into the global travel network. But one of the biggest patches closest to the city is due east just outside Perote, Veracruz.

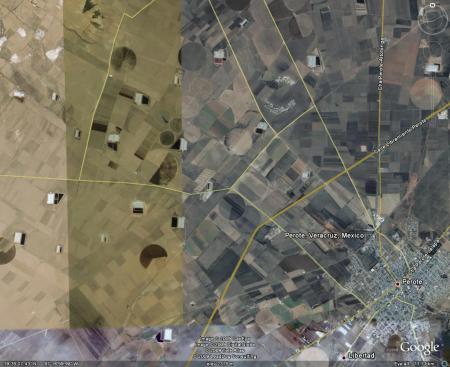

The Google Earth shot in the middle of the post shows some of the large swine feedlot operations, some owned by a Smithfield Foods subsidiary, just outside of Perote and only thirteen miles north of La Gloria, where the first confirmed case of H1N1 swine flu was recorded.

Leave a comment